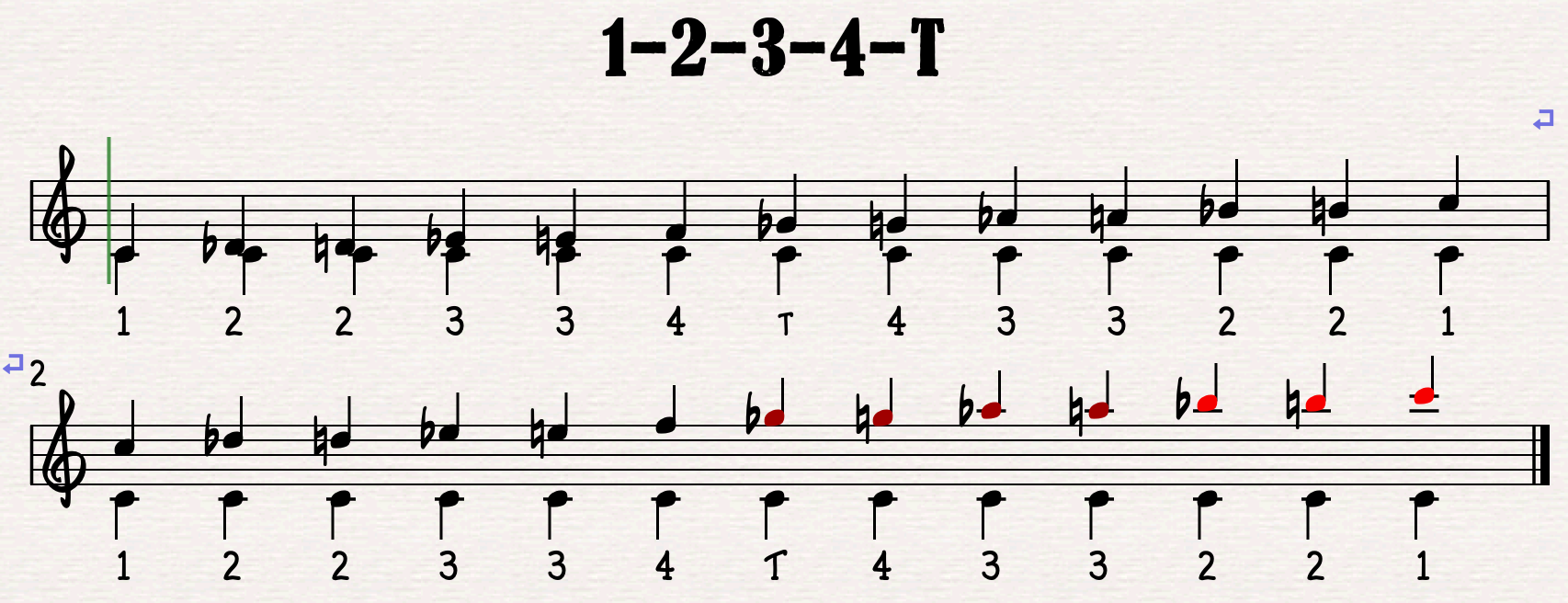

1-2-3-4-T

Real-time interval identification

This exercises categorizes the intervals into five groups: 1, 2, 3, 4 and T. Read below…

The Purpose of this exercises: “1-2-3-4-T”:

This is an exercise for helping you to develop “real-time” recognition of basic intervals: how to identify intervals without taking time to think, count or analyze them… that is, to know them with the same immediacy with which we recognize familiar colours. The graphic above shows how the intervals will be called for the first stage of this exercise.

The point of the exercise is that it presents a format for real-time listening, so if it works for you then you can substitute different values and turn it into something more relevant for your needs.

The graphic image (above):

This shows the five categories of intervals as they are used in this exercise. It is not intended as a theoretical model of consonance and dissonance, although the interval categories are in general agreement with most of the theorists who have written about the subject.

The Rationale for this exercise:

It’s easy to find the one red pair of socks in your sock drawer because most people can easily recognize the colour red. How do we do it as quickly and effortlessly as we do? Probably the most important thing is that we do not have to think about it; we know it by the direct sensation of the colour red. And how do we do that?

We can’t really ascertain ‘red’ by actually counting the vibrations; nor can we measure the angstrom units that would confirm which ones are the red ones. And I don’t imagine that we do it by comparison, unless there are many red socks of varying hues. I don’t think we have time to reason that the red is ‘warmer than blue but somehow ‘deeper’ than yellow or orange. We have, over time, essentially learned or memorized the general sensation of redness. Maybe we do this by association with something we know is red, such as a red traffic light or a fire engine, but it is still a direct sensation requiring no analysis. This exercise answers the question: Can we do this with intervals and other rudimentary musical values?

The Unison Exercise (in this website’s Rudiments category) is one model for training your quick listening skills that you can use with many variations to suit your specific needs. This “1-2-3-4-T” exercise has been of value to students over many years because it also develops “real-time” listening skills over a full spectrum of intervals. Once again, “real-time” simply means that you do not stop the music to think and analyze but you are developing the confidence to identify rudimentary values as you are listening—in the actual time of your listening. The exercise is simply called “1-2-3-4-T” and it can give you a head start in this direction.

When I began teaching musicianship and improvisation courses I did the same as I had always observed and experienced in classes by other professors. The teacher plays either one of the notes of the interval followed by the other, or the two are played together and sustained long enough for the students to try to absorb them. The students usually then sing them (aloud or inwardly) one at a time and then they often sing the steps in between, counting them in order to name the interval. This “1-2-3-4-T” exercise may give you the confidence to forego reliance on that mechanical method.

The theoretical basis for this exercise approach:

This exercise uses the most commonly expressed impressions of the different intervals: perfect unisons and their compounds, perfect octaves, are the most consonant. All seconds and their inversions (sevenths) and compounds (ninths) all share a related quality of dissonance. While minor seconds and minor ninths are usually considered more dissonant, for this exercise we begin by regarding 2nds, 7ths and 9ths as a certain related quality, a ‘family’ of dissonance. All thirds, sixths, tenths and thirteenths are also a kind of family of sensations, and perfect fourths, fifths, elevenths and twelfths also share a certain quality.

Theorists do not all agree on which are the most consonant or dissonant intervals. [A wonderfully informative and concise read for anyone interested is “A History of Consonance and Dissonance” by James Tenney.] For practical reasons, I have avoided considerations regarding the function of intervals (i.e., how they operate in musical contexts) nor do I include distinctions of the intervals’ quality, such as major, or minor. [In our equal tempered tuning system, an isolated augmented fifth sounds identical to a minor sixth, and that distinction does not enter into this exercise.] So, as described above, this exercise uses the following five categories of intervals that can be gleaned from the chart at the top of the page (and from the following descriptions):

“1” Unisons and their ‘compounds’ (octaves)

“2” Seconds, their inversions (sevenths) and their compounds (ninths)

“3” Thirds, their inversions (sixths) and their compounds (tenths and thirteenths)

“4” Perfect fourths, their inversions (perfect fifths) and their compounds (P11s and p12s)

“T” Tritones (augmented fourths and diminished 5ths) and their compounds (A11the & d12ths)

The first pair of columns on your answer sheet are for you to mark if the interval you hear was a category ‘1’ (unison or octave) or a ‘2’ (second, seventh, ninth), and you will make an answer for each of the 25 intervals. The next pair of columns, labelled 2s & 3s, has spaces to identify the 35 intervals you’ll hear. Each one will be either a ‘2’ (2nds, 7ths, 9ths) or a ‘3’ (3rds, 6ths, 10ths, 13ths).

The next pair of columns asks us to distinguish between category 3 and 4 and then finally between 3 and “T.” (T stands for Tritone.) The last four pairs of columns include all five categories: 1, 2, 3, 4 and T. If it seems too difficult, you can use one of the slower tempos or go back to the previous columns where you are only distinguishing between two categories.

The tempo is designed to go too fast to give you time to think or calculate, so don’t become anxious if the intervals move along too fast to give you time to respond as carefully as you’d like. The intervals don’t sustain or stop long enough to allow you to think, and scrolling backwards will be awkward. You may feel that you’re making too many mistakes; that you’re just guessing. And if you really don’t know then just guess. It will be interesting to see how quickly your ‘guesses’ become increasingly accurate. This is an intentional aspect of the exercise. It is designed to discourage reliance on thought and for you to begin to trust a more intuitive response which will be no less accurate than if you think and analyze. So if you feel that you’re just “guessing,” that is intentional. After many years, when I do it, I still feel that I am only guessing, but I see that my guesses now produce almost flawless results. Just as with picking out the correct colour from the clothing drawer, I rarely make a mistake. I have educated my sensory brain and it works so much faster than my intellectual brain. This is true for most of us in many situations, as stopping for a red light when we drive. So it’s like any sensory dependent skill—bike riding, scrambling eggs with a fork or even dialing the phone number of someone you have called a thousand times. The body just does it while the thinking mind only looks on or is distracted doing something else entirely.

Below is a spreadsheet for recording your answers, and I encourage you to customize your own. (You should also consider making your own recording of intervals.) There are also two pages with notation of the actual intervals that were played as well as the answers, i.e., the category of the interval.

I recommend tallying your scores because each time you do the exercise, they will improve and that is the desired result: perception of improvement.

Here is the slowest playback for the intervals and this one has only categories 1 & 2. It should be dead simple, but you may have to get used to the format of the exercise.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1uOr-eHH9L0nqaq9jwSAzbk6giS89JGK9/view?usp=sharing

If you’re interested in working with this, you can see some of the other files that accompany this stage of the 1-2-3-4-T exercise: Real-time listening 1-2-3-4-T

Filename: Contents (These are not active links, just file names.)

1-2-3-4-5 graphic.png

The chart displaying the interval categories

1 & 2 (from 1234T) @50.mp3

Four files of only 1s and 2s (i.e., audio examples of interval categories 1 and 2) at 50 beats per minute as well as 30 bpm, 40 bpm, 60 bpm

* 1 2 3 4 T (piano) @30.mp3

The last stage of this exercise, where intervals of all categories are mixed.

It is also played at 40 bpm, 50 bpm, and 20 bpm. Do all the other files first.

1-2-3-4-T Intro.docx

That’s the file you’re now reading.

2 & 3.mp3

A sequence of 25 intervals only from categories 2 and 3.

2 & 4.mp3

A sequence of 25 intervals only from categories 2 and 4.

3 & 4.mp3

A sequence of 25 intervals only from categories 3 & 4.

3 & T.mp3

A sequence of 25 intervals: either a ‘T’ (tritone) or from category 3.

1234T (LAST SECTION) @20.mp3

This file has all interval categories mixed together

1234T (LAST SECTION) @40.mp3

This file has all interval categories mixed together

1234T (LAST SECTION) @50.mp3

This file has all interval categories mixed together

1234T (LAST SECTION).mp3

This file has all interval categories mixed together

Record your answers here: [1234T]

And here are the correct answers along with the score:

Rationale:

When we listen to music for enjoyment we don’t usually waste any energy analyzing what we hear. But sometimes we hear an amazing chord or a provocative rhythm and we want to know what it is. We might want to use it for our own work or we might simply be curious.

Much of the time, we let it go because we’d rather keep listening than trying to go back for repeated hearings. That is one good reason to sharpen and speed up our listening and analyzing skills but there’s another important reason. When we play with others it’s good to know, with some precision, what they’re playing. Then we can play more intelligently and more sensitively with them.

So how to ‘speed up’ our perception of music while it’s in flow? Mostly how to be able to quickly identify such rudimentary values as simple intervals and chords – especially if we do not have perfect pitch?